"Today, I danced with Pygmies." Journal entry, 31 Oct 06. Last New Year's Eve, Dave and I talked about what we thought the coming year might hold. That was one experience I definitely did not see coming.

If the people of Rakai are poor, then the pygmy villages I visited are utterly destitute. I have never seen such squalor up close. Alone in one of their huts, I could hear the rats. Large ones closing ranks on me. It was all I could do to stand and hold the camera still for the long exposures in the lightless dwelling. As a rule, rodents don't freak me out, but I was becoming unnerved. I scanned quickly for light, color and composition — trying to remain calm to protect the long exposures — and I definitely did not linger.

If the people of Rakai are poor, then the pygmy villages I visited are utterly destitute. I have never seen such squalor up close. Alone in one of their huts, I could hear the rats. Large ones closing ranks on me. It was all I could do to stand and hold the camera still for the long exposures in the lightless dwelling. As a rule, rodents don't freak me out, but I was becoming unnerved. I scanned quickly for light, color and composition — trying to remain calm to protect the long exposures — and I definitely did not linger.A few pieces of soiled, tattered clothing hanging on a crude clothesline strung across the room. Deep, heady smells of earth, smoke and charcoal. A chicken enters the doorway, pecks around freely then absently wanders out. A charred pot sits alone. A sicle stands against a wall. A solitary shoe. An indiscernible mound of cloth lies in one of the darkest corners.

These pygmies are part of the Batwa tribe, forest dwellers whom the government has driven out of the Bwindi Forest (also known as the Impenetrable Forest) to make it marketable for eco-tourism. Specifically, gorilla trekking. They were unceremoniously escorted out, without being given places to live, ways to earn a living, or any guidance in matriculating into the mainstream society in which they suddenly found themselves. They are part of a tribal group with scattered remnants throughout the forest crossing into Rwanda and the DR Congo.

Brian Henderson, an American videographer, and I visited two of the Batwa settlements at the invitation of Hurinet (Human Rights Network) and AICM (African International Christian Ministry). AICM has been actively involved in helping the Batwa find their way into modern society. (Visit http://www.aicm.org.uk/index-Batwa.htm for more information). We were accompanied by Rangu from Hurinet, Doreen from AICM, and Guma, our driver.

Just getting to the villages was an amazing adventure. It took two to three hours in a 4-wheel drive on dirt roads that were often no more than gullies just to get to the footpaths that led up, straight up, severely straight up, to their settlements near the forest edge. The roads wound up into steeply terraced mountains that reach up out of Lake Bunyonyi. These routes are highly trafficked, not by cars but by people. People with farming implements. People driving cattle. People herding goats. People carrying things on their heads: laundry, produce, bundles of branches, furniture. People speeding downhill on bicycles. People walking bicycles uphill. And the bicycles would have all manner of things strapped to them: other people, produce, a goat, a bed.

And, despite sitting in the way back of the four-wheel drive, with four other Africans in the car, the passersby would invariably shout out "Mzungu!" and run towards us for a look. I felt like my name was Elizabeth and I was paying a state visit.

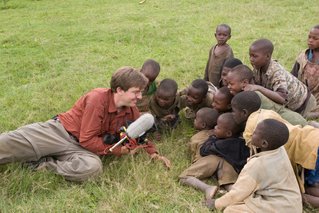

The first day we visited a settlement of about 40 Batwa in an area just on the forest edge. AICM has built a school up in the village as the closest goverment school is too far to be accessible. The children crowd the school building and seem eager to learn: dutifully copying their work onto slate boards, repeating the English phrases spoken by their teacher, and singing songs. Later, when Brian was interviewing village leaders, the children would edge up to me asking for books, for money, for pens. Anxious to keep them quiet, I led them off a bit and got them to sing some songs (quietly) for me. They loved singing "head and shoulder, knee and toe" while I would always point to the wrong body part. I'm anxious to hear Brian's sound bytes from his interviews as I wonder how successful I really was at keeping them quiet.

At first, they did not want me to take their pictures. They would shy away whenever they would see my camera raised. After our impromptu singalong, however, even the women seemed to warm up. They slowly wandered over to the group of children around me, anxious to see what was going on with the crazy white woman. After Brian's interviews ended, it seemed a celebration was in order as the adults gathered together and broke out in their traditional dance: replete with singing, drums, and the high jumps their dance is known for. I couldn't shoot fast enough. Their joy was totally infectious. I shot from a small hill above. I shot at their level. I laid on the ground and shot their feet. It was exhilarating!

At first, they did not want me to take their pictures. They would shy away whenever they would see my camera raised. After our impromptu singalong, however, even the women seemed to warm up. They slowly wandered over to the group of children around me, anxious to see what was going on with the crazy white woman. After Brian's interviews ended, it seemed a celebration was in order as the adults gathered together and broke out in their traditional dance: replete with singing, drums, and the high jumps their dance is known for. I couldn't shoot fast enough. Their joy was totally infectious. I shot from a small hill above. I shot at their level. I laid on the ground and shot their feet. It was exhilarating!

The second day, we visited a different settlement of Batwa, equally difficult to get to. This was the group that allowed us inside one of their homes. Doreen is truly dedicated to these villagers. And you can see the utmost trust and respect that they have for her. Upon our arrival, she would explain the nature of our visit and how we wanted to share their plight with those who could help them. Still a bit mistrustful of us, they would slowly relax and open up. This second group lived up a particularly steep path that wound back and forth like a switchback to make the height a bit more manageable. Once into the village (this one had about 20 - 25 adults), we were shown how they make baskets. Beautiful, large baskets. But they sell them to the local villagers for about 50 cents, and those villagers turn them around for about $10. The Batwa see none of this profit. The health concerns here are worrisome as well. As they all sat listening to the speeches made by their leader and the visitors, I noticed a girl whose nose was bleeding, without any thought by her or those around her. At the end of our visit, I was nurse to Guma who used my first aid supplies to clean out a deep, ugly wound in an older lady's hand which was badly infected. Just the previous day, Doreen was quite upset to discover a woman who's leg had become so badly infected the gaping wound was now about 8 inches in diameter. There was much discussion as to whether the woman refused treatment or her husband had, and what was now going to be done about it.

The second day ended in the memory of my lifetime... after dressing the woman's wound, Guma and I headed down the steep path to catch up with the others in our party. As on the previous day, these people had danced and sang for us as well. Only now, the singing and dancing continued as we made our descent. The children ran ahead of me, skipping and jumping down the path. I followed, imitating them as best I could, camera in each hand held high in case I took a dive. The womem followed behind, singing in their exhuberant voices, some beating jerry cans, all of them swaying down the path behind me smiling broadly.

We danced all the way down to the car, then continued to dance for another 15 minutes. They would laugh when I got the clapping wrong, and they cheered when I jumped high, tucking my legs tightly under as I had seen them do. The most animated woman danced with me, around me, dodging under my upraised arms. Totally mesmerizing.

Finally herded back into the car, I had a short break before we reach our next stop: a local government school to which AICM sends two Batwa boys showing promise as future leaders. As before, while Brian conducted interviews, I wandered around capturing glimpses into a totally foreign society. These government schools are crude at best. Very basic buildings, no doors or windows, furnished with benchs, desks, and chalkboards. I think of how our schools feel the pinch of budget cutbacks. And I am in disbelief at how well these kids listen, learn, thrive and grow with the sparse resources available to them.

Many Batwa children came onto the campus when the saw the Mzungus arrive. There is a stark disparity between the cleanliness of the school children in their brightly colored uniforms and the Batwa children in their brown, tattered rags. I easily capture images of the two groups together. I also see the irony in a group of the Batwa playing under the Ugandan flag. If only their government were truly looking over them instead of overlooking.

Once again, children provide the highlight of the visit. While sitting on the ground with a small group of the Batwa, a large contingent of schoolchildren suddenly converges on us and I am engulfed by seated, kneeling, standing kids. At least forty in all. The back of my arms are gingerly touched. Fingers stroke my hair. The heady smell of poverty threatens to overwhelm me. Once all of the children had closed in, I tried to get them to sing as the kids did the previous day. However, everything I said was promptly parroted about. "Can you sing me a song?" I asked. "Can you sing me a song?" they replied. "No, you sing!" I demanded. "No, you sing!" came the response. "Okay" I said. "Okay" said they. "How are you?" (How are you?). I am fine. (I am fine). I have to sneeze. (I have to sneeze). Aaahh-choooo! (Aaahh-choooo! followed by peals of laughter). "Hyperbole." (Hyperbole). "Oxymoron." (Oxymoron). "Onomatopaeia." (Onomonooa...... trailing off to barely heard mumbling). How much fun!! I loved to see them laughing and so carefree.

Really, after the images of stark poverty, I remember the sounds of joy and laughter. Now, I need to somehow reconcile the two.

By the time we returned to our base in Kabale on this second day, it was too late to head back to Kampala. Brian was really crunched for editing time as the end of the workshop loomed nearer. However, final translations needed to be done with Doreen and Ugandans are loathe to drive at night for several reasons. Two of them are compelling enough: many people drive without lights, and up until a few years ago this area of Uganda had been subject to marauding groups of ex-soldiers comandeering vehicles as they struggle up the hills at night: robbing everyone inside and occasionally killing the occupants. So, we were more than content to wait until morning to make the 6-hour trip back to Kampala.

Space (and attention spans) prohibit me from detailing all of the remarkable experiences I had just in the area of day to day living. One day in Kabale, I asked the lady at the front desk if I could have some laundry done. She leaned over the desk to look outside and said "Yes. It's sunny today."

The first night we arrived in Kabale, Brian and I looked skeptical at the hotel chosen for our stay. I told Brian that after Rakai, all I required was a room with a working outlet (for recharging batteries), hot water (and I didn't care whether it was above the toilet or not), and a bed without bugs. The floor no longer mattered. As it was, this hotel ended up having excellent fish (although the first night the English Fish, the Classic Fish and the Grilled Fish all came out looking the same) and a nightly showing of Nigerian movies in the restaurant. That first night we (Brian, myself, Rangu and Guma) all stayed up way too late totally immersed in the high family drama of whether the fathers would allow their children to be together or if their feuding would end in the brother's death. And could the dying brother (hit by a car driven by the other father's driver) reconcile them before he drew his last breath? Yes, it seemed he could.

It is my fervent hope that the people I've met will result in relationships that will last my lifetime. Rangu is returning to Zimbabwe where human rights are precarious indeed with the current government. Guma is working his way through school while supporting his mother, sister and two brothers. He is studying business and writes business proposals as a way to supplement his income. The Batwa have touched his heart as well, and he's working on a plan we've discussed at length to form a visitor center at the entrance to the Bwindi forest which would educate tourists about the Batwa and provide an outlet for the Batwa to sell their crafts profitably. Doreen has recently married, and only sees her husband on weekends so she can continue to work with the Batwa through AICM. I have a lot of photos for Brian, and I understand he has some video clips for me. Both of us have been encouraged by this experience to continue to pursue projects highlighting overlooked people and issues.

One more entry to this blog should complete my Uganda experience. The workshop ends, and I have Guma take me to Murchison Falls to spend my last few days in Uganda before heading to Dubai. Rest? Relaxation? Stay tuned.